FDA Proposing New Definition of 'Healthy' in Food Labeling

"Healthy' is one of those words like "natural." It means something but the meaning is so broad as to be nearly meaningless. This leaves food manufacturers free to label their food as healthy without providing much in the way of proof.

The Food and Drug Administration hopes to change that with its newly proposed definition of “healthy,” which would set new limits for added sugars, and new minimum levels of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, dairy, and protein, in products that would bear the voluntary “healthy” marketing claim.

The proposal would also allow water and no- or low-calorie carbonated water to qualify as “healthy” beverages.

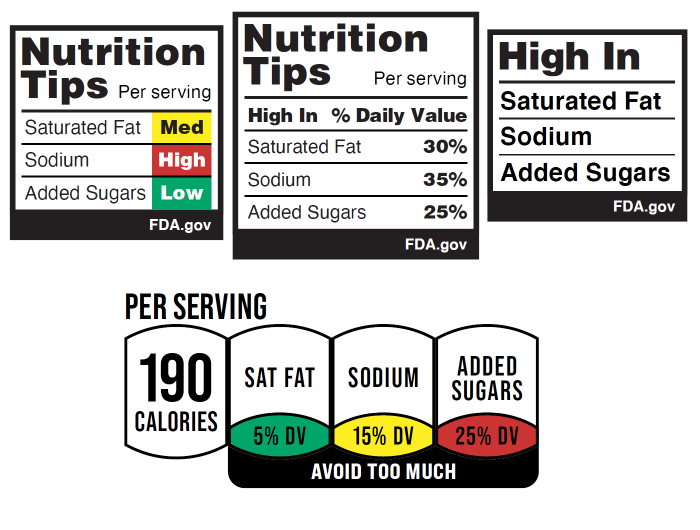

In January, the agency released draft images of what the new labels might look like, shown above.

The proposal is a "substantial improvement over the status quo," according to the Center for Science in the Public Interest. The nonprofit nutrition and food safety watchdog group today praised the new limits but told the FDA in comments submitted to the agency that the proposal could be improved by strengthening the whole grain, fruit, and vegetable requirements, and by ensuring that terms like “wholesome,” “nutritious,” and “heart healthy,” are considered implied “healthy” claims.

However, even with additional improvements, the actual benefits of the “healthy” claim to consumers would be limited. According to the FDA, about 15 percent of products qualify for the current definition of “healthy,” and less than five percent actually bear the claim. The agency further estimates that after the improvements are implemented, only four percent of foods in the grocery store might carry the claim.

CSPI says, in effect, that it might be better to require large warnings on foods that are unhealthy.

“While the FDA’s proposed definition of ‘healthy’ is an improvement, the term is best understood as a marketing claim, and a voluntary one at that,” said CSPI senior policy scientist Eva Greenthal. “Companies are already skilled at marketing the purported health benefits of their products. But what about the information they don't want you to know? FDA should focus on mandatory measures to ensure companies highlight both the nutritional benefits and drawbacks of their products."

There's evidence that front-of-package nutrition labeling can improve consumer understanding and encourage healthier diets. Dozens of countries, including Canada, Mexico, Chile, and more, have already implemented interpretive front-of-package nutrition labeling.

After Chile implemented its octagonal, front-of-package nutrient warnings, sugar consumption plummeted by more than 10 percent. The law also caused companies to reformulate their products. Chile also saw a significant 7 percent reduction in products that were high in calories, sugar, sodium, or saturated fat across the country’s packaged food supply, with a particularly high 15 percent reduction in products high in sugar.