FDA Wants to Get Lead Out of Baby Food

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is announcing a new program intended to reduce lead levels in food for infants and children under two.

Lead is not something babies should be exposed to in more than trace amounts, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is announcing a new program intended to reduce lead levels in food for infants and children under two.

“For more than 30 years, the FDA has been working to reduce exposure to lead, and other environmental contaminants, from foods, said FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, M.D. “For babies and young children who eat the foods covered in today’s draft guidance, the FDA estimates that these action levels could result in as much as a 24-27% reduction in exposure to lead from these foods.”

Thirty years may sound like a long time and, indeed, in January 2017, an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) draft report indicated that food is a meaningful source of children’s exposure to lead.

Later that year, the Environmental Defense Fund analyzed the EPA report and found that, "over 1 million young children consume more lead than what the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers acceptable for children to eat every day."

The EDF said that eliminating excessive lead from food would mean that "millions of children would live healthier lives, and the total societal economic benefit would exceed $27 billion a year in increased lifetime earnings resulting from the impact of lead on children’s IQ."

Foods with the most lead

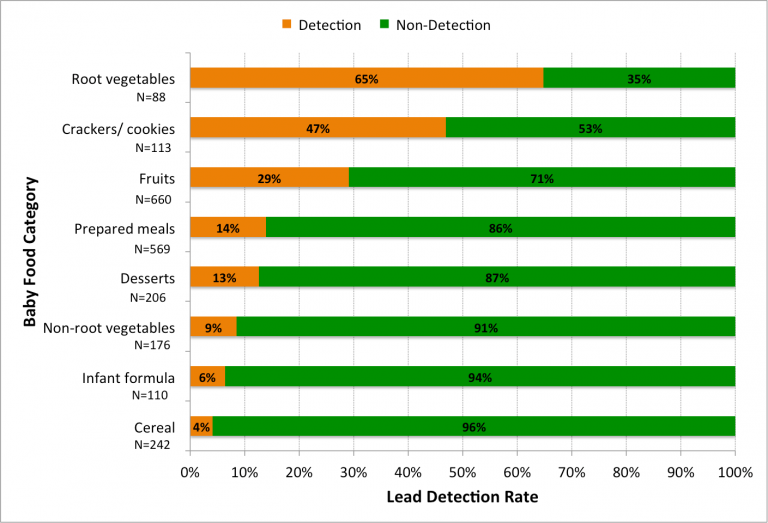

The EDF said its study found that 20% of 2,164 baby food samples and 14% of the other 10,064 food samples had detectable levels of lead. At least one sample in 52 of the 57 types of baby food analyzed by FDA had detectable levels of lead in it. Lead was most commonly found in the following baby foods:

- Fruit juices: 89% of 44 grape juice samples contained detectable levels of lead, mixed fruit (67% of 111 samples), apple (55% of 44 samples), and pear (45% of 44 samples)

- Root vegetables: Sweet potatoes (86% of 44 samples) and carrots (43% of 44 samples)

- Cookies: Arrowroot cookies (64% of 44 samples) and teething biscuits (47% of 43 samples)

In addition, EDF said that lead was more frequently detected in samples of the baby food versions of apple juice, grape juice, and carrots than their regular versions.

Closer to Zero

The FDA's draft industry guidance are part of the agency's Closer to Zero program, which sets forth the FDA’s science-based approach to reducing exposure to lead, arsenic, cadmium and mercury to the lowest levels possible in foods eaten by babies and young children.

Foods covered by the draft guidance, officially named Action Levels for Lead in Food Intended for Babies and Young Children, are those processed foods, such as food packaged in jars, pouches, tubs and boxes and intended for babies and young children less than two years old. The draft guidance contains the following action levels:

- 10 parts per billion (ppb) for fruits, vegetables (excluding single-ingredient root vegetables), mixtures (including grain and meat-based mixtures), yogurts. custards/puddings and single-ingredient meats.

- 20 ppb for root vegetables (single ingredient).

- 20 ppb for dry cereals.

Targets are "achievable"

The FDA said it considers these action levels to be achievable when measures are taken to minimize the presence of lead.

The problem is that lead, like other harmful substances, occurs just about everywhere, both as a natural element and from pollution resulting from industry, transportation and agriculture.

Just as fruits, vegetables and grain crops readily absorb vital nutrients from the environment, these foods also take up contaminants, like lead, that can be harmful to health.

The presence of a contaminant, however, does not mean the food is unsafe to eat. The FDA evaluates the level of the contaminant in the food and exposure based on consumption to determine if the food is a potential health risk. Although it is not possible to remove these elements entirely from the food supply, FDA said it expects that the recommended action levels will cause manufacturers to take measures to lower lead levels in their food products.

Not dietary advice

The FDA said its proposed guidance is not intended as dietary advice to parents.

“The action levels in today’s draft guidance are not intended to direct consumers in making food choices. To support child growth and development, we recommend parents and caregivers feed children a varied and nutrient-dense diet across and within the main food groups of vegetables, fruits, grains, dairy and protein foods,” said Susan Mayne, Ph.D., director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“This approach helps your children get important nutrients and may reduce potential harmful effects from exposure to contaminants from foods that take up contaminants from the environment,” she said.