Eviction Moratorium Ending, Leaving 8 Million Renters at Risk

This Saturday, July 31, marks the end of the federal moratorium on renter evictions, a protection put in place during the COVID pandemic, leaving both renters and landlords worried about what happens next.

The U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has published a guide to hundreds of rental assistance programs across the country.

“We will see a historic wave of evictions and housing instability this summer and fall” without further measures to protect tenants, said Diane Yentel, president and chief executive of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, in a Wall Street Journal report.

Tenants will face a huge bill for the rent payments they missed and many landlords are facing financial difficulties because the moratorium cut off their rental income but not their mortage payments, taxes and other expenses.

The U.S. Census Bureau reported recently that about 8.1 million renters were behind on their payments in mid-June, and another 4.5 million said they thought they faced eviction. Not all will be evicted, but as many as 4.2 million adults are at risk of eviction in July and August, according to an estimate by the Urban Institute.

Moratorium imposed last fall

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Sept. 4 2020 temporarily banned landlords from kicking out certain families from their homes, a protection that extended through this summer.

The moratorium had been set to expire on June 30 but CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky signed an extension through July 31 and said that was intended to be the final extension.

Some states and cities have extended the moratorium. New Jersey’s extension lasts for two months after the end of the emergency period. California has extended the ban through Sept. 30, New York through Aug. 31 and Hawaii through Aug. 6.

While the moratorium is providing a temporary respite from rent payments, it does not keep rent from accruing – meaning that tenants will be responsible for the rent payments they missed during the pandemic.

The moratorium doesn’t block all evictions. Tenants must prove they are making their best effort to make partial payments, and landlords can still evict tenants for damaging property or fighting with neighbors.

Confusing and unevenly implemented

Although unevenly implemented and confusing, the moratorium is credited with stopping – or at least delaying – millions of evictions. State and local governments struggled to distribute $47 billion in federal money aimed at helping tenants, and many eligible tenants and landlords were unaware the program existed.

News reports said many tenants had trouble filling out the application forms correctly, while others were unable to produce proof of their income.

The rent moratorium was available to renters who made under $99,000 in 2020, or couples who made under $198,000, were protected if they signed a declaration under penalty of perjury that if they were evicted, they would likely become homeless or be forced to live in crowded quarters, and that they were making an effort to make partial rent payments.

Evictions harmful to everyone

Obviously, being shut out of one’s home is traumatic for families. Besides losing their home, they often lose personal belongings, children’s education may be disrupted and adults can lose their jobs.

The Urban Institute estimates that if the 4.2 million adults who report being at risk of eviction in the next two months were actually evicted, it could result in a total of $6.6 billion in lost earnings (PDF) and $5.0 billion in increased debt (PDF) for those tenants.

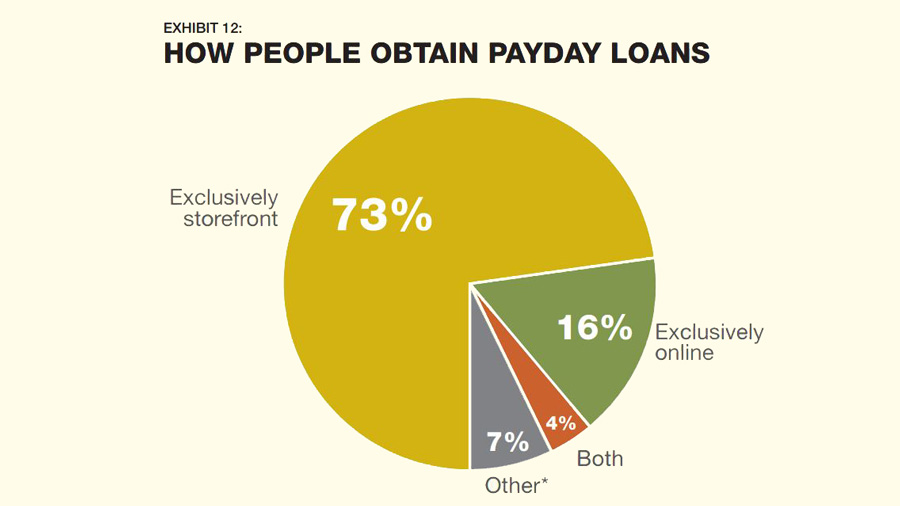

Evictions can also push lower-income households further into financial trouble if they turn to payday or title loans or other “alternative” financial services that often create an ever-growing mountain of debt. On average, 12 million Americans each year take out payday loans, and 7 out of 10 borrowers use them for regular expenses like rent and utilities, a Pew Charitable Trusts study found.

Evictions are also costly for landlords, who can accrue filing fees, lawyer costs, lost rent, and damages to units, the Urban Institute notes.

It estimated that if the 4.2 million adults who report being at risk of eviction in the next two months were evicted, it would cost landlords nationwide a total of $2.6 to $4.6 billion to serve and process evictions and between $8.0 and $50.0 billion in lost rent and repairs to units.

What can tenants do?

Tenants who have been making partial rental payments and who have kept their property in good condition during the moratorium should appeal to their landlord to negotiate a payment plan that lets them pay off the back rent over a period of one or two years.

The laws differ from one state and city to another but nearly all jurisdictions have programs in place to help low-income renters who are facing difficulties because of circumstances beyond their control.

Renters who have lost their jobs or suffered a pay cut because of the pandemic should have a strong case to present to their landlord and, if necessary, to a judge or other legal authority.

As the Urban Institute noted, evictions are expensive for landlords as well as tenants and most landlords want to hang onto good tenants. A tenant who has a good relationship with the landlord should be in a strong position to negotiate a favorable settlement.