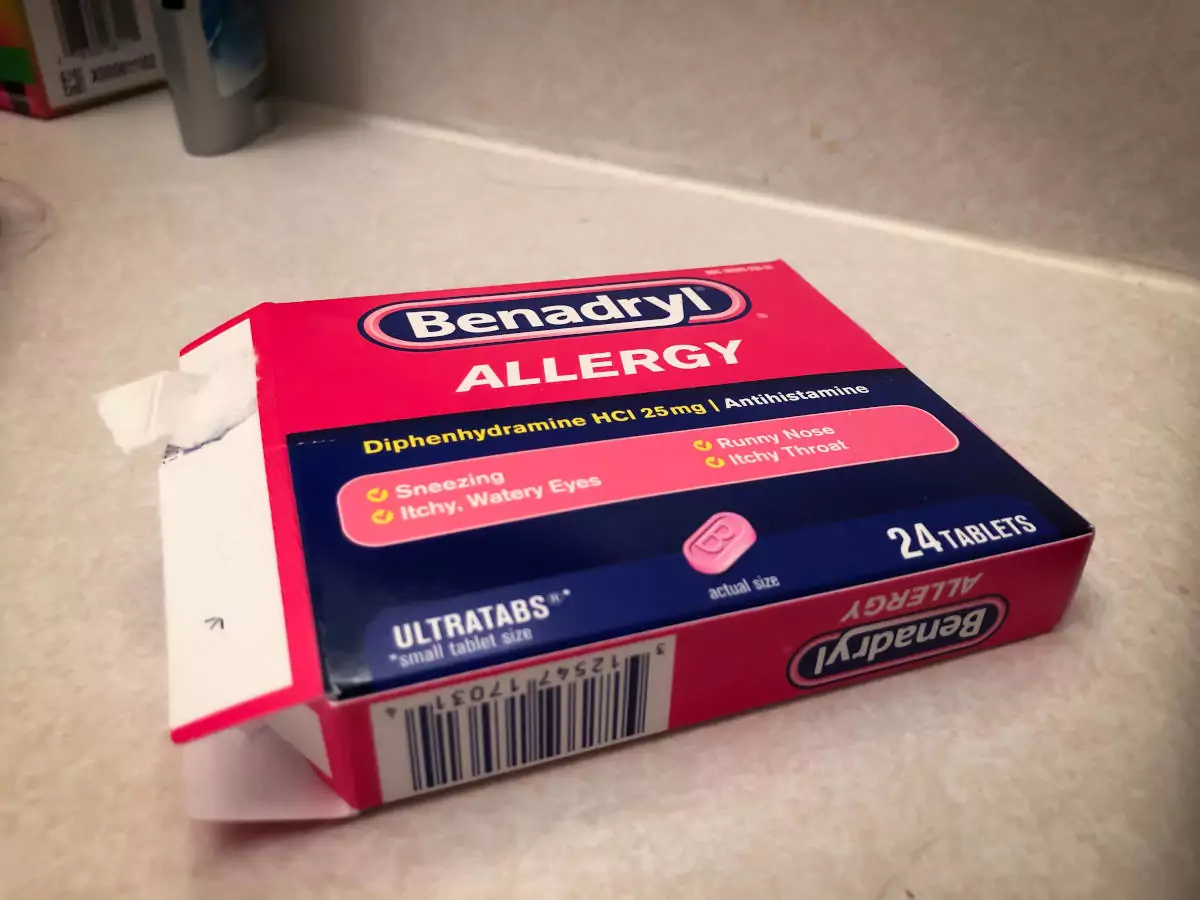

Benadryl Still Widely Used After Study Linked it to Alzheimer's

Given how much excitement there’s been about Aduhelm, a new drug recently approved to treat Alzheimer’s disease and how much money people spend on all kinds of unproven treatments, you’d think strong evidence linking certain popular drugs to the dread disease would get a lot of attention.

But strangely, that’s not the case. It’s been more than six years since researchers in Seattle found a “significantly increased risk” of Alzheimer’s and other dementias among people who have taken Benadryl (diphenhydramine), a popular over-the-counter drug used for the relief of allergy symptoms. But instead, sales of the venerable drug continue to be robust, ranking number five among OTC antihistamines, according to Statista.

“Older adults should be aware that many medications–including some available without a prescription, such as over-the-counter sleep aids–have strong anticholinergic effects,” said Shelly Gray, PharmD, MS, when the report was issued in January 2015. “And they should tell their health care providers about all their over-the-counter use,” she added, in a news release.

Anticholinergic drugs block the action of neurotransmitter chemicals released by nerve cells to send signals to other cells, possibly interfering with memory and cognition.

“No one should be using Benadryl as a routine allergy medication.” — Roy Benaroch, M.D.

Gray was the first author of the report, which tracked nearly 3,500 Group Health seniors participating in the long-running Adult Changes in Thought (ACT), a joint Group Health-University of Washington (UW) study funded by the National Institute on Aging.

Confirmed earlier Alzheimer’s studies

Earlier studies had found the link between Benadryl and Alzheimer’s but the Seattle study used more rigorous methods, longer follow-up (more than seven years), and better assessment of medication use via pharmacy records (including substantial nonprescription use) to confirm the link.

The study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, was also the first to show a dose response, linking more risk for developing dementia to higher use of anticholinergic medications. And it was also the first to suggest that dementia risk linked to anticholinergic medications may persist–and may not be reversible even years after people stop taking the drugs.

Devastating consequences of dementia

“Given the devastating consequences of dementia, informing older adults about this potentially modifiable risk would allow them to choose alternative products and collaborate with their health care professionals to minimize overall anticholinergic use,” the JAMA report cautioned.

But for whatever reason, the study didn’t receive the front-page attention normally devoted to promising new treatments for dementia, many of which never get beyond the promising phase. It is mentioned now and then, but mostly in publications for medical professionals and those in related fields, like a 2019 article in the Harvard Health Blog.

“One long-ago summer, I joined the legion of teens helping harvest our valley’s peach crop in western Colorado,” wrote Beverly Merz, executive editor of Harvard Women’s Health Watch. “My job was to select the best peaches from a bin, wrap each one in tissue, and pack it into a shipping crate. The peach fuzz that coated every surface of the packing shed made my nose stream and my eyelids swell,”

Merz’s family doctor fixed her up with some Benadryl and Merz wrote that she was very thankful for the relief it offered.

“Today, I’m thankful my need for that drug lasted only a few weeks,” she wrote, saying that Gray’s study offered “compelling evidence of a link between long-term use of anticholinergic medications like Benadryl and dementia.”

“The … results add to mounting evidence that anticholinergics aren’t drugs to take long-term if you want to keep a clear head, and keep your head clear into old age,” Merz said. “The body’s production of acetylcholine diminishes with age, so blocking its effects can deliver a double whammy to older people.”

Time for Benadryl to retire?

Many doctors seem not to be aware of the Seattle team’s findings. A Washington, D.C., allergist and faculty member at a leading D.C. medical school, recently assured an elderly patient that it was fine to take Benadryl before bed every night, both for relief from allergies and as a sleep aid.

“If it works for you, by all means, take it. It’s not habit-forming and the benefits likely outweigh any risks,” he said.

But some other physicians are becoming quite outspoken on the subject.

“It is time for that old drug to be retired, sent off to pasture, and never used again. Goodbye, Benadryl. Fare thee well, adieu, and don’t let the door hit you on the way out,” said Roy Benaroch, M.D., in a February 2020 essay in Medshadow.

“Benadryl (diphenhydramine) was introduced in 1946. The top single that year was Perry Como’s ‘Prisoner of Love,’ and, with all due respect, neither has aged well,” Benaroch said. “Back in 1946, medicines like Benadryl didn’t have to pass the stringent safety and efficacy standards now required. And there’s zero chance, today, it would have been approved for over-the-counter sale. Even if it made it as a prescription medicine, it would be plastered with warning labels.”

“Newer and better alternatives to treating any allergic disease are Zyrtec (cetirizine), Claritin (loratadine) and Allegra (fexofenadine). These are all safer, faster, and more effective,” Benaroch, a North Carolina pediatrician, said.

“There is no situation where Benadryl is a better choice as an oral antihistamine. No one should be using Benadryl as a routine allergy medication,” he wrote.